Introduction

Organizational structures in schools have, for the most part, remained the same for decades. Schools have one overall leader overseeing, well, everything. This not only leads to a concentration of power and control, but it also often leads to an overload of responsibility and workload for that person in charge. The school’s success depends on the one person in charge. If they stand the school stands, if they fall, the school falls, too. Many theories and models have been suggested to distribute that load, some with more success than others. What most of them have in common, however, is that they leave one person in overall charge of the school, no matter how much team leadership is introduced. After all, “there must be a boss, someone who calls the shots when needed”, or does there?

This essay will explore a different option. A leadership model that truly creates team leadership, where solutions are found together, and decisions are made by consensus. For some, it will seem similar to what they are used to already, for others it will seem unrealistic if not impossible. I encourage all readers to engage in the following thoughts with an open mind.

Beyond the Principalship

The way it has always been

The labels of a school leader have changed over time and today different ones are being used depending on school size, host culture and context – principal, director, head of school, just to mention a few. Adding to this semantic confusion is that the same titles are used for different roles. In one school there is a principal and then heads of elementary, middle and high school, in another school the same roles might be called head of school, and then principal elementary, middle and high school. What stays the same, however, is that it is one person in charge of the school, and that is a very complex affair. It always has been and Rousmaniere (2009) puts it very well:

The school principal is the most complex and contradictory figure in the pantheon of educational leadership. The principal is both the administrative director of educational policy and a building manager, both an advocate for school change and the protector of bureaucratic stability. Authorised to be employer, supervisor, professional figurehead, and inspirational leader, the principal’s core training and identity is as a classroom teacher. Standing squarely between state institutions and the classroom, assigned both to promote large-scale initiatives and to solve immediate day-to-day problems, the principal carries multiple and often contradictory responsibilities, wears many hats, and moves swiftly between multiple roles in the course of one day. A single person, in a single professional role, acts on a daily basis as the connecting link between a large bureaucratic system and the individual daily experiences of large number of children and adults. (Editorial, para. 1)

Decades ago, in village or small-town settings, while nonetheless complex, this might have been manageable for one person. Today, schools become ever bigger organisations and new models of leadership must be developed. Unfortunately, it seems that many schools find themselves stuck in this historical model of leadership.

The principal

So, who are these principals, these one man or woman do-it-all school leaders? Usually, they are teachers. Excellent educators that are then promoted into leadership. Sometimes, especially in large schools, they are business managers with exceptional corporate skills, brought in to move the school forward. And often, unfortunately, they are people who thrive on power and control (Botha & Fuller, 2021). What most of them have in common is that they are good in one of the areas described by Rousmaniere (2009) but lack substantially in others due to the sheer size of scope of their job these days. They sit at the top of the still common traditional organizational chart, overseeing everything.

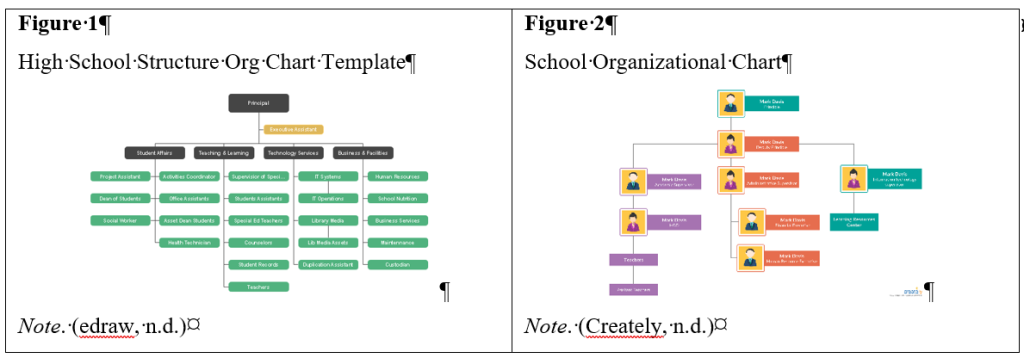

The traditional organizational chart of a school

Any quick google search for “school organizational chart” will render results similar to figures 1 & 2. There are variations to this, some with a board inserted to the side between the principal and the rest of the organization or some having deputy roles between levels. Many are organized so that the principal and the top-level head of departments form an executive leadership team. Nevertheless, the school leader is at the top of the chart which is organized in a classic top-down manner.

It is up to each school to further define their leadership model and incorporate more distributed and participatory models. However, it seems that no matter how flat the leadership of a school is structured, there still needs to be a big boss who is in charge of it all. In this paper, I would like to propose an alternative.

The Team3 Model

The Team3 Model has developed quite naturally over the past four years as part of pioneering our own school in Vanuatu. It is heavily influenced by Youth With A Mission’s foundational value No. 10 (Youth With A Mission, 2022) – Functioning in teams. While my own experience of successful YWAM leadership teams is limited, it was often the large size of those teams or the fact that there was still an overall leader, that made real success difficult. There is, however, a different example that has been successful for many decades – the Swiss Government. The executive, the elected seven state ministers or federal councillors, run the state affairs by consensus. There is no prime minister with the power to appoint and reshuffle their cabinet. While each minister oversees their respective department, executive decisions are made as a council by consensus (Hendriks & Karsten, 2014 and Ladner & Sager, 2022).

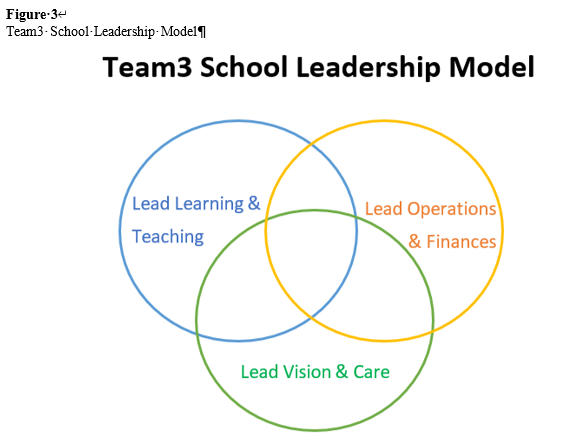

As our school grows, we are establishing an executive leadership team called Team3 where there is not one principal or head of school. Instead, the three leaders, each overseeing a particular area of the school, lead together and make decision by consensus. In here lies the difference to a traditional leadership team. The three leaders form the executive leadership team without one of them having more power or authority than the others. There is not one principal, director or head of school who is over department heads that together form the leadership team. Whenever their circles of responsibility overlap, they must work together and make decisions by consensus, not by voting or deferring to the one in charge. The circles are dynamic and can change in shape and size, and so do their areas of overlap depending on the situation at hand.

This model is derived from a flat leadership model that has then appropriate structure built on it (George, 2016). Several advantages of this model stand out. The success and failure of the school does not rest upon one person. Parallel to this, the power and control over the school does not rest with one person either. Leadership, responsibility and accountability are actually distributed. In today’s large schools, the three areas defined in the model – Vision & Care (Pastoral), Learning & Teaching (Academic) and Operations & Finances (Business) are each so specialised that they require experts to lead them. Expecting that one person can truly give leadership to all of them is unrealistic, so why have one person over them? And which one of the three would end up with the top job? Or does it end up being a fourth position whose sole job it is to coordinate the teamwork of the other three? Either way it is a sub ideal solution. In contrast, the Team3 model empowers all three of them to lead the school together. Another advantage with the Team3 model is continuity. Tenure in leadership positions is increasingly short-lived which can lead to big challenges and lack of continuity in a school with traditional school leadership. With the proposed Team3 model, when one of the leaders transitions out of the organization, two thirds of the leadership remain and can guarantee continuity as a new member is recruited and introduced.

While this model is still being established at our school, we already see the principle of it trickle down to the teachers and admin staff who also work as teams and find solutions together rather than expecting a boss telling them what to do. Currently, since our school is still small, the overlap of Learning & Teaching and Vision & Care is large, and the administrative workload is limited. However, as much as possible and where practical, processes and decision making are already delegated to members of the team. Even with the small size of our school, not having to do all three of the circles in the illustration makes a big difference for the involved leaders.

Challenges

The main criticism and challenge with this leadership model is that it creates slow and irresolute decision making. However, in the context of a school, the extra time it takes for the three leaders to find consensus on a matter will hardly ever be detrimental to the success of the school. The advantages of leading a school as a team by consensus will virtually always outweigh this time argument.

Weak or even lack of leadership is another argument brought against this leadership model. The bigger the leadership team gets, the more likely this has validity, however, with three members only, this will hardly be an issue. It is also an argument rooted in the traditional understanding of leadership where there must be someone calling the shots. As understanding of leadership is changing quickly, less opposition from this can be expected and where it still exists it is worth challenging.

Conclusion

Education is crucial for any society and the education system is under immense pressure from many sides. School leadership is likely among the most challenging career fields in today’s world. Unlike in the corporate world, changes and developments of school leadership models are slow and met with resistance from all around.

Considering the very specialized and vastly complex areas of competencies in school leadership the traditional model of one person in charge of the entire school is often inadequate, leading to an inefficient and ineffective organization, to misuse of power by the school leader, or to burnout of the school leader. Attempts to distribute the responsibility and power to a team has been done countless times with varying success, but most of these attempts leave one person in charge of the team thus not really changing the model.

The Team3 school leadership model proposes a fundamental change in the way schools are run. With leading the school by consensus, the three executives share the burdens according to their fields of expertise, increasing the level of effective decision making. Accountability is also increased as no major decisions can be made alone. Furthermore, continuity in leadership is improved since one executive leaving the organization will not mean a complete shift in leadership. The remaining members of Team3 will continue to steer the school on the given track and incorporate a new team member as they are recruited.

School leadership in the 21st century is facing extreme challenges and new ways and new models must be found to move forward. I believe the Team3 school leadership model makes a valuable contribution towards these efforts.

References

Botha, J., & Fuller, M. (2021). South African teachers’ views of the power and control exercised by their principals. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603124.2021.1942993

Creately. (n.d.). School Organizational Chart. Pinterest. https://www.pinterest.ch/pin/464011567855172236/

George, Drake, “Trust & Growth in the Workplace: an Analysis of Leadership in Flat Organizations” (2016). University Honors Theses. Paper 353. https://doi.org/10.15760/honors.341

Hendriks, F., & Karsten, N. (2014). Theory of democratic leadership. P.’t Hart & R. Rhodes (Eds.), Oxford handbook of political leadership, 41-56.

High School Structure Org Chart Template. (n.d.). Edraw. https://www.edrawsoft.com/template-high-school-structure-org-chart.html

Ladner, A., & Sager, F. (2022). 29. Switzerland: the politics of PA in a multi-party semi-direct consensus democracy. Handbook on the politics of public administration, 321.

Rousmaniere, K. (2009). Historical perspectives on the principalship. Journal of Educational Administration and History, 41(3), 215–221. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220620903080645

Youth With A Mission. (2022, November 8). The Statement of Purpose, Core Beliefs and Foundational Values of YWAM – Youth With A Mission. Youth With a Mission. https://ywam.org/about-us/values